KU Giving Magazine

Team Spirit

MICHELLE TEVIS

Partnerships between advisors and donors create a winning plan for giving

Sports and estate planning have a notable element in common: teamwork.

The University of Kansas has a long record of teams lighting up the scoreboard. Equally strong is the legacy of generous donors who have helped shape KU into the premier institution it is today. A team of advisors can help donors create a plan to support the areas of the university that spark passion.

The players can vary depending on a donor’s goals, and a team can include financial planners, attorneys, tax consultants, KU Endowment and the university itself. All players agree that a strong relationship between the donor and team members is essential to making the donor’s vision for their legacy into a reality.

Cathy Reinhardt, a financial advisor and president of Reinhardt Financial Services Inc., in Lawrence, says her role is to give people the tools they need to give in a satisfying way.

“Because of the relationship we’ve built, I can gauge what’s reasonable for them to give,” she said. “For clients interested in philanthropy, I sometimes push them to up their game.”

A game plan

For Elizabeth Schultz, KU professor emerita of English, making her gifts come to fruition meant working with Reinhardt, KU Endowment and the university. Together, they planned several gifts, including scholarships supporting the humanities and the arts and a distinguished professorship in English.

“Cathy has always been very receptive to any ideas,” Schultz said. “And then she knew how to make them happen.”

Lewis Gregory, senior vice president and private client advisor at Bank of America Private Bank in Kansas City, Mo., finds success in identifying areas where the donor truly feels connected.

“From there, we narrow that so their gift can have a major impact, as opposed to giving to a lot of different entities,” Gregory said. “We next decide the best way to implement it so their giving is effective.”

The vehicles through which someone can structure their legacy are many. There isn’t a one-size-fits-all approach.

Calling the plays

Donors may not know they can create detailed instructions for how a gift is used, Reinhardt said. When gifts are made, donors approve a fund administration agreement that documents precisely how they want the funds to be spent.

“I imagine that some people give very generously, but to KU at large,” Schultz said. “For me, that isn’t as personally fulfilling as it is to designate gifts to very special projects.”

She and Reinhardt worked together to develop specific gifts that benefited areas important to her, notably the Herman Melville Distinguished Professorship in the Department of English, where she was a professor for 34 years before retiring in 2001.

“Working with the department makes it very personal and meaningful to me,” she said. “And anyone can do it. A gift can be given anywhere in the university.”

UNLIMITED OPPORTUNITIES: KU professor emerita of English and donor Elizabeth Schultz, pictured on a trip to the Mekong Delta in Vietnam, says giving to KU offers endless possibilities and tangible results. “Your gift isn’t abstract,” Schultz said. “You can see it being used and appreciated.”

Photo by Elizabeth Schultz

Photo by Elizabeth Schultz

Feel-good feedback

Donors have the option of giving charitable gifts that are used during their lifetimes. Seeing gifts transformed into actual experiences and educational fulfillment can be a gratifying motivation for donors.

“Giving at death misses the joy a gift can bring to someone’s life,” Reinhardt said.

Schultz established the Janet Hamburg Dance Scholarship fund that memorializes Hamburg, a professor of dance at KU and an internationally known movement analyst and lecturer. Schultz wanted to remember Hamburg and also to support the dance program, which is small. Her gift provides scholarships to incoming dance students.

“That’s been very satisfying, and I’ve gotten to know some of those students personally,” Schultz said.

Passing the ball

Discussing philanthropy as a family gives parents an opportunity to model their values for their children. Parents who talk about their interests and set an example with giving have the chance to instill those values in the next generation. Even young children can learn from activities such as volunteering, saving money and making donations to charity.

Brad Korell, attorney and partner at Korell & Frohlin in Austin, Texas, says family dynamics play as big a role in gift planning as tax laws do. Charitable giving discussions could be an important part of a family’s overall financial education. Not only does it better equip children to make philanthropic choices, it also puts them in the position of knowing how to handle their parents’ finances if the need arises.

“When parents have involved their children, whether about the family business or overall plans, it makes a transition go much smoother,” Korell said.

Reinhardt advises clients to work on philanthropy as a family and use giving as a teaching tool. “You are not born a philanthropist,” she said. “You learn it.”

Get in the Game

To make your own gift planning playbook, visit kuendowment.org/planmygift or contact Andy Morrison at 785.832.7327 or email.

Current Issue

Issue 38

Spring 2024

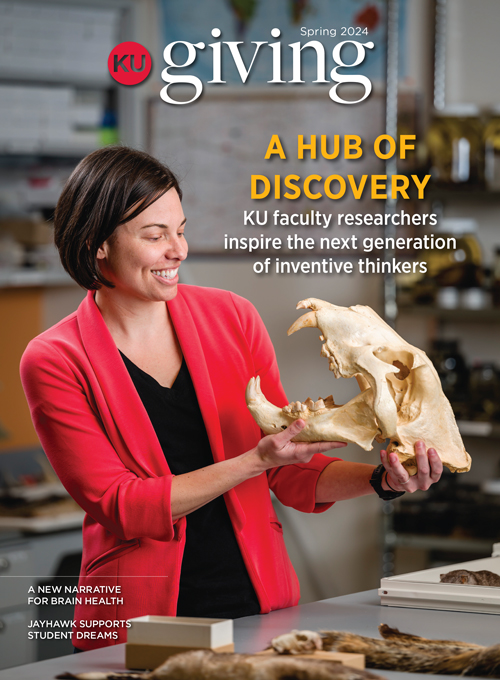

In this Spring 2024 issue, we meet faculty and student researchers who are uncovering clues about how organisms change, learn about exciting brain health developments at the KU ADRC, experience a unique study abroad program and get to know inspiring KU students, faculty and alumni.