A Bountiful Season on the Prairie

Anne Tangeman

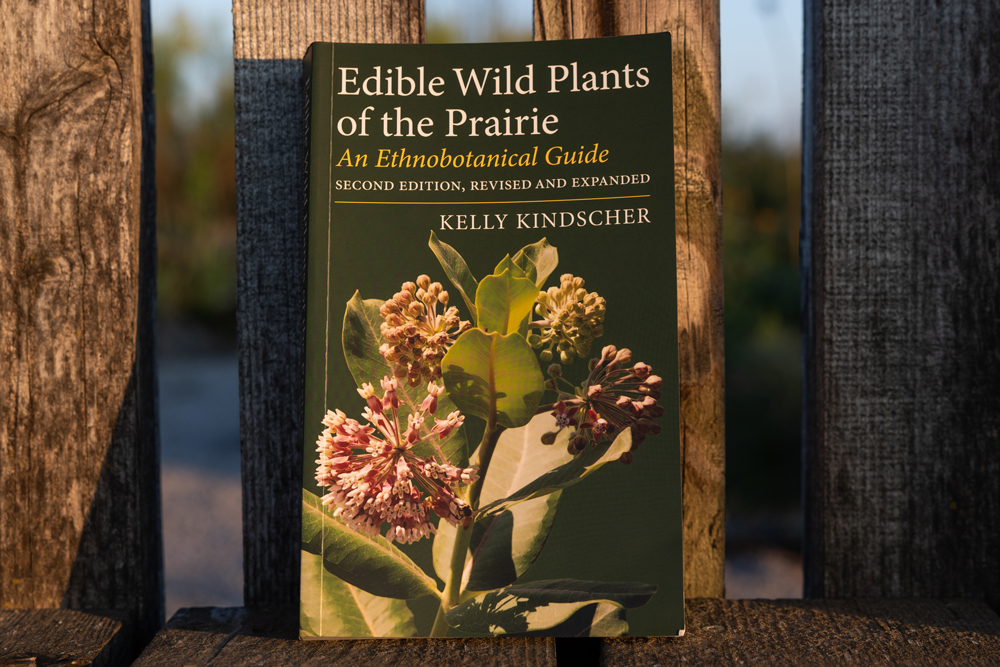

KU professor publishes new book on edible plants.

When the University Press of Kansas approached Kelly Kindscher three years ago about creating a new edition of his iconic first book, “Edible Wild Plants of the Prairie: An Ethnobotanical Guide,” first published in 1987, he had a simple answer for them — no.

A month later, the senior scientist at the Kansas Biological Survey and Center for Ecological Research and professor in the Environmental Studies Program changed his mind, realizing he had more to say. There were new native plant species and variants to add, a deeper understanding of plant ecology and uses to share and, he says, something more important.

“There are different cultural approaches now, and the new version better acknowledges traditional ecological knowledge,” said Kindscher, whose work over the last four decades has involved numerous, ongoing collaborations with Native American tribes through his ethnobotany research on the human uses of plants, medicinal plant research, sustainable harvests of native plants and prairie restoration work.

In addition to updating the title sections for indigenous plant names from “Indian Names” to the preferred “Native American Names,” he added plant monikers used by the Arikara, Comanche, Kansa, Plains Apache and Ho-Chunk (Winnebago) Tribes to the new edition.

The new edition features more than 119 additional entries on less common plant species and especially in groups of species, such as plums and onions. Descriptions of plants, uses, stories and new maps with better distribution data are paired with lush color photographs, most of which he took himself, to help the reader more accurately identify species.

Kindscher’s favorite edible wild plant of the prairie is lambsquarters.

“I feel I need to educate people that this weed is also a prairie plant and a favorite cooked spring green – with salt and butter. Yum.”

The Syracuse, Kan., native’s respect for the prairie bioregion and his never-ending sense of curiosity are reflected in the book and have been at the heart of his work since he was young. He first learned about prairie plants from his father during summers working on his family’s homesteaded farm near Guide Rock, Neb., which he and his brother now own.

“I delight in learning about plants and am fascinated about human-plant interactions, especially around food and medicine,” he said.

Kindscher followed his growing passion for plants to KU, earning his undergraduate degree in the burgeoning Environmental Studies Program in 1979. After graduation, he stayed in Lawrence, doing carpentry and odd jobs, with no thoughts of graduate school. A long walk with a friend, Vicky Foth, changed all that.

“We both had interest in exploring the region, so we took the summer to walk from Kansas City to the Rocky Mountains, doing about 10-12 miles a day.” Along the 690-mile route of unpaved roads and wild areas, he noted plant species in a journal and his interest brought more questions. His love of writing also grew and his path to study ethnobotany, or the interrelationships of humans and plants, emerged.

“I quickly realized I needed to learn about plant use from people who were here before and in that way, another type of conservation was realized,” said Kindscher. “There needed to be conservation of indigenous knowledge.”

He turned the notes from the journal into his first book and went on to earn both his master’s degree and doctorate in systematics and ecology at KU, now in the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. He’s been a researcher with the KU Biological Survey and Center for Ecological Research since 1992 and a professor in the Environmental Studies Program since 1996. He also serves as a courtesy associate professor in the Indigenous Studies Program, ecology and evolutionary biology and geography, in addition to providing faculty guidance to a variety of KU student groups and clubs.

Kindscher’s new book, an updated edition of his classic 1987 work, is now available from the University Press of Kansas.

Much of Kindscher’s varied work changes with the seasons, from fieldwork in Colorado and New Mexico in the summer and fall, to teaching environmental studies in the spring and research and grant writing in the winter.

This is a particularly busy season. Along with the book release, Kindscher was presented with the George B. Fell Lifetime Achievement Award from the Natural Areas Association at the group’s national conference in October. He was also recently awarded two research grants, both of which include opportunities for KU students.

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) awarded Kindscher a two-year, $400,000 grant to add Native American names and plant uses to the USDA Plants Database. Funding within the grant will provide for collaborative work with five tribal nations language programs in the first year. A new KU Indigenous Studies Program graduate student in Kindscher’s lab, George Growingthunder (Assiniboine/Dakota), will be working with him on the project.

The United States Forest Service also awarded Kindscher a two-year, $180,000 grant to collaborate with Midwest tribes to create databases of edible, medicinal and pollinator-friendly plant species for future restoration projects of prairie and open canopy sites on U.S. Forest Service lands. Additionally, the grant supports a two-year fellow for the program, which brings former KU undergraduate Kahheetah Barnoskie (Pawnee) back to KU.

“It has the longest title of any grant I’ve ever received: Restoring with Culturally Significant Plants to Strengthen Food Webs for Pollinators and Tribal Community Well-being,” said Kindscher. He added that a greater awareness of the importance of pollinator species has had an effect on his work, though it was a surprise to him.

“I never would have thought that small bees and butterflies might drive some of our restoration of prairies,” he said.

His research on the medicinal properties of plants also continues, including one he’s studied throughout his career: echinacea, or purple coneflower, a native prairie plant taken in various forms by many people to boost immunity and ward off colds. He currently has 800 echinacea plants growing at the KU Biological Survey’s Field Station for a study funded by ExAlt™ R&D, LLC to investigate potential beneficial seed properties. The plot is overseen by Lisa Castle, who joined the Kindscher Lab and Native Medicinal Plant Program last year and is also a lecturer with the Environmental Studies Program. She is a former student of Kindscher’s who earned her doctorate in ecology and evolutionary biology at KU in 2006.

“He’s the expert on prairie ethnobotany,” said Castle. “He uses his knowledge to make connections and is very good at spreading rather than sequestering information.”

Sharing knowledge through teaching is also central to Kindscher’s work, and his impact is prolific, from drawing students to the fields of ecology and environmental studies to mentoring them through projects, fieldwork and on to careers. Students interested in working with him beyond the classroom are often supported through KU scholarships, including the Environmental Studies Program’s Zadigan Scholarship, which provides funds for undergraduate research opportunities. Students may work at the KU Native Medicinal Plant Garden at the Field Station or assist in the Native Medicinal Plant Program office or lab. He often draws on these students when seeking assistants for fieldwork in Colorado or New Mexico.

These experiences have led alumni to varied careers in environmental work and across academics. Todd Aschenbach, who earned both his master’s degree and doctorate at KU in ecology and evolutionary biology, is a professor of natural resources management at Grand Valley University. He was an environmental consultant in 1996 when a brief chat with Kindscher at a conference led him to graduate studies at KU. He says his former mentor has a unique ability to engage wide audiences in conservation.

“Kelly masterfully combines both the science and art of studying natural areas,” Aschenbach said. “His research addresses important questions, but he’s adept at telling the stories of natural areas and the plants that inhabit them — their past, present and future.”