Return of the Guardians

Michelle Strickland

KU unveils reimagined grotesques that have stood watch over Dyche Hall for 114 years

KU unveils reimagined grotesques that have stood watch over Dyche Hall for 114 years

It might not be polite to call a beloved work of art “grotesque.”

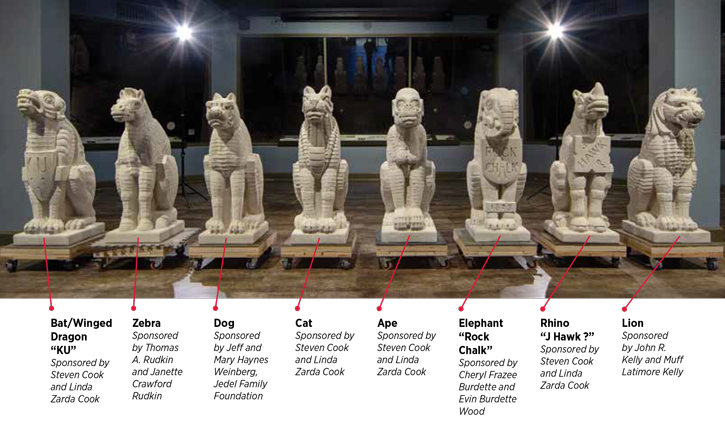

But for Cheryl Frazee Burdette, her grandfather’s stone sculptures adorning Dyche Hall at the University of Kansas were just that: grotesques, or fantastical figures, carved to sit atop 12 pedestals on the north, east and south sides of the building.

The animalistic guardians, from an ape to a zebra, were installed during the construction of Dyche Hall in 1903. Joseph Roblado Frazee, with help from his son Vitruvius, created them from lower Cottonwood limestone, a fine-grained, bright-white stone quarried in Kansas.

When Burdette was a freshman at the University of Kansas in 1957, she passed Dyche Hall as she walked to class from her dorm room at Gertrude Sellards Pearson Hall.

“It made me smile and filled me with pride to see the beautiful carvings on this building, knowing my grandfather was the sculptor,” Burdette said. She followed in her grandfather’s artistic footsteps, earning a fine arts degree and enjoying a 30-year career as a fashion illustrator. Now retired, she lives in Lenexa, Kan.

Four sculptures were removed in 1963 when an addition was built on the north side of Dyche Hall. They went into storage on West Campus, and one, thought to be a goat, went missing or was stolen, and its whereabouts remain a mystery. The remaining eight kept their watch over Jayhawk Boulevard until 2017, when a renovation of Dyche Hall revealed the grotesques’ heartbreaking erosion from 114 years of exposure to brutal Kansas weather.

WEATHER-WORN: The original grotesques were beyond repair after more than a century at their post.

Why these creatures?

Gargoyles (different from grotesques in that they have open mouths and sluice water) sit atop European cathedrals such as Notre Dame in Paris and were thought to be guardians of the sacred world. In that way, Leonard (Kris) Krishtalka, director emeritus of the KU Biodiversity Institute & Natural History Museum, believes the grotesques at Dyche Hall were meant to be guardians of the natural world who watch over the work happening inside the museum.

There are no paper records that offer insight or indicate what each of the animals might represent. The Rhino’s “J Hawk ?” shield adds to the mystery: it is unclear what the question mark means.

“We decided to take them down to preserve them for history,” said Leonard (Kris) Krishtalka, director emeritus of the KU Biodiversity Institute & Natural History Museum, housed in Dyche Hall. “They are unique to Kansas, unique to the university and unique in the United States.”

It also was decided they should be re-created, Krishtalka said.

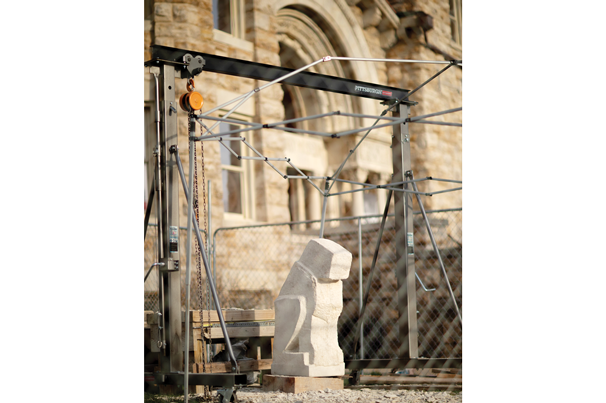

As the crumbling grotesques were carefully wrapped, boxed and lowered by crane, the Grotesque Renewal Project began to raise private funds to replace the creatures.

The museum requested proposals for resculpting the grotesques, and the winning proposal came from Lawrence artists (and siblings) Laura and Karl Ramberg and KU School of Architecture & Design associate professor and adjunct lecturer (and spouses) Keith and Amy Van de Riet. All four are KU alumni, and the Rambergs credit influence from teachers Bernard “Poco” Frazier and Elden Tefft for their love of sculpting.

The Van de Riets focused on the grotesques for a class in the historic preservation program at KU’s School of Architecture & Design. Their students used photogrammetry to take measurements of the original grotesques through photos, then made 3-D printed models. The Rambergs did the sculpting.

The education aspect set their bid apart, Krishtalka said. Karl Ramberg made rough carvings out of the large blocks of limestone in a fenced area in front of Dyche Hall, where the university community could watch his progress. Students from a variety of majors — from architecture and design to fine arts — assisted in the initial carving and 3-D modeling. Karl Ramberg spent about 40 to 50 hours roughing out each limestone block; once the blocks were cut, Laura Ramberg took over. She referenced one-quarter scale models and made blueprint-like drawings with exact measurements to guide her air hammer, ensuring the new carvings were faithful to the originals. Each grotesque took her about 165 hours and eight weeks to carve.

“I had to treat myself like an athlete,” Laura Ramberg said in a video conference celebrating the completion of the statues. “It was important to pace myself because there were several to do, and it was labor-intensive and very focused work.”

All eight grotesques were completed by November 2020. More than 80 donors, including the Historic Mount Oread Friends, gave to the overall rejuvenation project. Some donors “adopted” grotesques with major gifts.

Steven Cook and Linda Zarda Cook of Houston adopted several grotesques: the cat, the ape, the bat/winged dragon and the rhino, which are all on the front (east side) of Dyche Hall.

When the Cooks heard about the poor state of the statues, they decided to contribute to the project. Linda, a KU alumna from the School of Engineering and a KU Endowment trustee, said after a visit during which they saw the deteriorated grotesques in person, they decided to adopt four.

“It’s a bit like deciding to get a puppy, and when you go to the adoption center, they’re all so cute, you end up coming home with two or more,” she said.

Linda said giving to KU has always brought her joy, and she has typically given to general funds and allows the university to direct the use of her gifts to where they’re needed most. But she couldn’t resist the chance to support something “more tangible.”

“You just don’t get that many chances in life to adopt a grotesque!” she said.

Cheryl Frazee Burdette and her daughter, Evin Burdette Wood, adopted the elephant, which bears a shield on its chest that says “Rock Chalk.”

Burdette says one of the most important aspects of this project, to her, is the recognition her grandfather is receiving for his skillful, creative work.

“Now people will know his name and hopefully remember it,” she said.

She felt a wave of passion propel her toward giving to the project, not just because of her family connection, but because she wanted to be involved in something greater than her own world and gain a deeper connection to her alma mater.

That connection, manifested through family, art, architecture and beauty, is one Burdette hopes will encourage more students to choose KU and find as much love for the university as she has.

“Beauty is good for the eyes and great for the soul, even on a college campus,” Burdette said.

And, thanks to the generosity of many, the reimagined grotesques will continue their predecessors’ watch over the natural world as their fierce beauty draws new generations of eyes up in curiosity and wonder.

The following KU students participated in the grotesques project as part of the historic preservation program within the School of Architecture & Design.

- Megan Bruey, Architecture

- Victoria Gonzalez, Architecture

- Andrew Hutchens, Architecture

- Elizabeth Overschmidt, Architecture

- Jacob Peterson, Architecture

- Sarina Shanks, Architecture

- Sarah Thomas, Museum Studies

- Jordyn Tobias, Architecture

Photo by University of Kansas/Andy White

Photo by University of Kansas/Whitney Young

Photo by University of Kansas/Andy White

Photo by University of Kansas/Whitney Young

Photo by University of Kansas/Andy White

Photo by University of Kansas/Andy White

Photo by University of Kansas/Andy White

Photo by University of Kansas/Meg Kumin

Photo by University of Kansas/Andy White

Photo by University of Kansas/Andy White

Photo by University of Kansas/Andy White

Photo by University of Kansas/Andy White